🌳 Why Mangroves?

The coastal CO₂ vaults where forests meet sea

🌎 Understanding Natural Capital

Natural capital refers to the stock of natural resources—such as soil, air, water, and living organisms—that provide ecosystem services essential to human well-being and economic prosperity. Ecosystem services are defined as “the benefits people obtain from ecosystem functions, characteristics, or processes that contribute directly or indirectly to human well-being” (Costanza et al., 1997; 2011; Millennium Ecosystem Assessment, 2005a).

🌳 Understanding Mangroves

Mangroves, once dismissed as wastelands, are salt-tolerant trees and shrubs thriving in tropical and subtropical intertidal zones like estuaries and river deltas. They are renowned for offering a wide array of ecosystem services. These include food production, raw materials, climate regulation, pollution control, coastal protection, recreational opportunities, and spiritual experiences, among others (Millennium Ecosystem Assessment, 2005b; Russi et al., 2013).

In Costa Rica, mangroves are overseen by the National System of Conservation Areas (SINAC, for its acronym in Spanish), an institution that has conducted numerous studies on the socioeconomic value provided by these ecosystems.

According to SINAC (english version), the most prominent and impactful ecosystem services provided by mangrove forests in the Gulf of Nicoya are:

🌾 Provisioning Services

These services include all material goods that ecosystems provide to humans. In the case of mangroves (according to the document you shared), they include:

🍤 Food: Production of fish, shellfish, and other marine products.

🪵 Raw materials: Wood, firewood, tannins, and other natural materials.

🌿 Medicines: Use of plants and marine organisms with healing properties.

🧬 Genetic materials: Biological resources for biotechnology and genetic improvement of commercial species.

🚰 Drinking water supply: Through natural water filtration.

🌎 Regulation Services

These services maintain ecosystem balance and regulate natural processes, protecting biodiversity and human communities. In mangroves, they include:

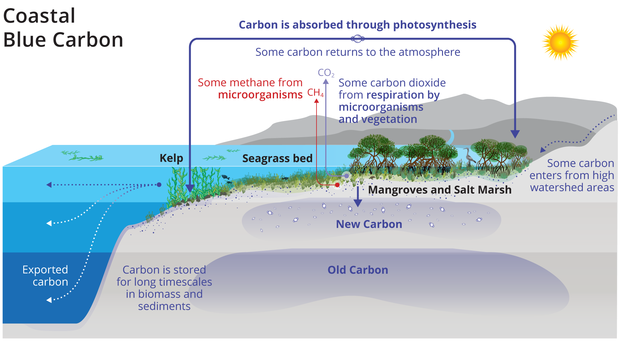

🌡️ Climate regulation: CO₂ storage and sequestration, helping mitigate climate change.

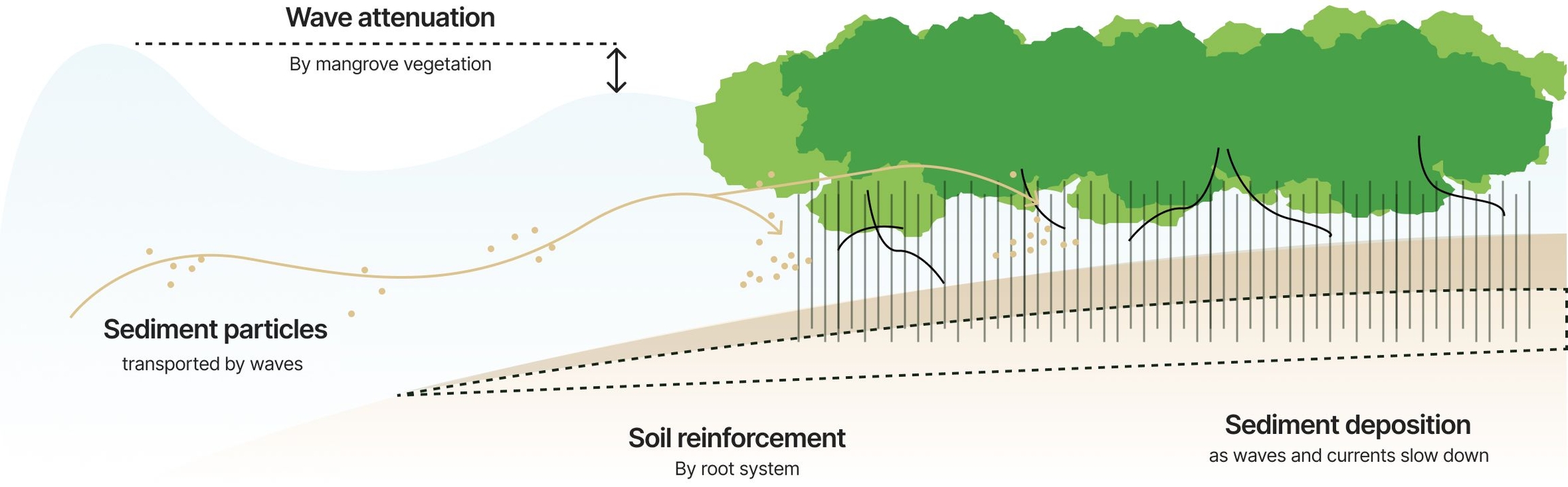

🌊 Coastal protection: Reducing the impact of storms, tsunamis, and coastal erosion.

💧 Water cycle regulation: Filtration and purification of water, helping maintain its quality.

🧪 Pollution control: Absorption of pollutants, nutrient detoxification, and improvement of water and air quality.

🐞 Biological control: Regulation of pests and diseases through ecological interactions.

🌄 Cultural Services

These are non-material benefits that ecosystems provide to people through experiences, values, and knowledge. In mangroves, they include:

🏝️ Recreation and tourism: Spaces for activities such as recreational fishing, ecotourism, and hiking.

🌅 Aesthetic value: Inspiration for art, photography, and nature appreciation.

📚 Education and research: Opportunities for scientific studies and environmental learning.

🧘 Spiritual and cultural values: Importance for indigenous communities and other cultures in their traditions and beliefs.

🌱 Supporting Services

These are fundamental ecological processes that enable the existence of other ecosystem services. In mangroves, they include:

🦜 Biodiversity maintenance: Providing habitats for various marine and terrestrial species.

♻️ Nutrient cycle: Recycling of organic matter and natural fertilization of the soil.

🪨 Soil formation: Sediment retention and contribution to soil stability in coastal areas.

🐝 Pollination: Supporting plant species and nearby crops through the presence of pollinators.

Many of these services function as public goods (Brander et al., 2012). This means they are non-rival—one person’s benefit does not reduce another’s—and non-excludable, making it difficult or impossible to prevent people from benefiting from them. This contrasts with private goods, which are both rival and excludable (Barbier, Acreman & Knowler, 1997; Costanza, 2008).

Markets are inherently better suited for private goods. As a result, the public-good nature of many mangrove ecosystem services—particularly regulating and cultural ones—means they are often undervalued or completely unpriced in traditional economic systems (Brander et al., 2012). This leads to inadequate market incentives for their preservation and a bias in favor of land-use conversions that offer short-term, monetized benefits.

Consequently, mangroves are frequently undervalued in cost-benefit analyses comparing conservation with commercial land uses (Salem & Mercer, 2012; Acharya, 2002), contributing to their global degradation and loss. To counter this, comprehensive valuation of mangrove ecosystem services is essential for sustainable management and protection. Furthermore, a combination of market-based and non-market institutional mechanisms is required to effectively conserve and sustainably manage these critical ecosystems.

Mangrove forests cover less than 0.1% of the Earth's surface yet provide vital ecosystem services worth an estimated $2.7 trillion annually. They protect coastlines by buffering erosion, reducing storm surges, stabilizing sediment, and filtering pollutants to enhance water quality.

Mangroves also serve as nurseries for endangered species, support fisheries and aquaculture, and generate income through ecotourism. Additionally, mangroves supply raw materials like honey, timber, and medicinal resources, making them an irreplaceable natural asset with intrinsic value.

⚠️ Present-Day Challenges

As we grapple with urgent environmental challenges, forest conservation stands out as one of our most critical issues. Forests cover about one-third of the Earth’s surface and play a vital role in maintaining biodiversity, supporting livelihoods, and regulating the climate.

Yet, they are disappearing at an alarming rate. The Earth loses around 38,610 square miles of forest every year, with tropical forests being particularly vulnerable, as they account for 96% of global deforestation. Since 1990, the planet has lost over 1 billion acres of forest to various human activities such as agriculture, livestock farming, and industrial development.

Deforestation, driven by illegal logging, agricultural expansion, and urbanization, continues to degrade these essential ecosystems. The loss of forests contributes to climate change by releasing stored CO₂ and destabilizing weather patterns while also endangering countless species.

To maintain a balanced, healthy, and stable planet, we must protect 30% of Earth’s most biodiverse areas by 2030. Yet, nature conservation faces an annual funding gap of over $100 billion. Today, half of the world’s GDP is highly or moderately dependent on nature, which is also inextricably linked to the climate. Acknowledging this interdependence, G7 leaders declared in 2021 that “our world must not only become net-zero, but also nature-positive—for the benefit of both people and the planet.”

Most mangrove forests are in developing countries where economic benefits often outweigh ecological concerns, leading to deforestation. This growing issue concerns both environmental advocates and global organizations. The 2024 IUCN Red List of Ecosystems reports that over 50% of the world's mangroves are at risk of collapse by 2050.

Without increased conservation, 7,065 km² of mangroves could be lost, and 23,672 km² submerged due to rising sea levels, resulting in a loss of 1.8 billion tons of carbon, costing $336 billion, and endangering 2.1 million people from coastal flooding.

Last updated